Ancient Mammoth Tusks = Cure for Modern Medicine

A 30,000 year old woolly mammoth tusks discovered in the Yukon may assist medical researchers in understanding bone diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis.

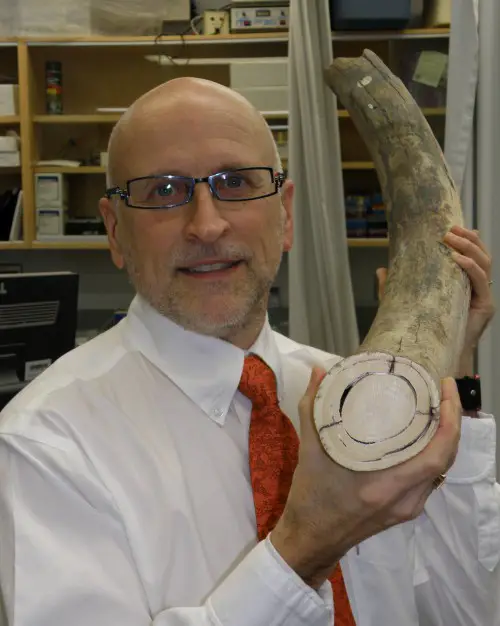

Stephen Sims holds the portion of mammoth tusk that will be used to research osteoclasts. Photo: University of Western Ontario

It is common for Scientists to use modern-day elephant tusks in order to conduct research into these bone-related problems. However, Stephen Sims, a Physiologist at the University of Western Ontario in Canada believes that these ancient mammoth tusks are better suited for these scientific purposes.

Professor Sims said, “Mammoth ivory is just a tool, but we think we can use this ancient tool for modern-day medical research.”

In humans, a cell called an osteoclast latches onto a bone’s surface. It will then secrete hydrochloric acid which will break down the bone mineral. In healthy bodies, bones are rebuilt again through an osteoblast. This process which is also known as bone remodelling is a balancing act of both formation and resorption. Sometimes excessive bone lost can occur.

If excessive bone lost occurs, this will lead to the fragility of the human skeleton and increase the risk of fractures. Many inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis are typically accompanied by excessive resorption which contributes to the pain and disability suffered by those with the condition. In addition, some cancers such as prostate and breast cancer are known to metastasise bones which will then lead to bone loss and pain.

With the mammoth tasks, Sims expects that it studying osteoclasts will become more transparent compared to an elephant. This is because it will allow for more exact monitoring of the cells. Both elephant and mammoth tusks contain dentin, which makes it easier to see through as it ages. Dentin is also found in human teeth, which is why human teeth are more transparent near the root rather than at the tip because it is the oldest part of the tooth.

Due to this, Professor Sims believes that the 30,000 year old dentin from the woolly mammoth tusk will be able to create more transparency than any researchers have seen or used before. He said that this would then allow researchers to see details more clearly about the resorption process than ever before in scientific history.

In order to carry out this theory, the tusk will be cut up into slices, about a third the thickness of human hair. Osteoclasts will then be applied on the ivory and incubated for a day or two as resorption continues.

If this succeeds, then this could make way for better drugs to treat those with bone-related illneseses, according to Paula Stern who is an osteoporosis specialist and a Professor of Molecular Pharmacology and Biological Chemistry at Northwestern University. “The existing drugs that we have are still not effective for some people, so we need to develop new and better drugs.”

Of course, developing these new and improved drugs for bone-related illnesses are a long step. However, both Sims and Stern believe that the forthcoming research from using the ancient woolly mammoth’s tusks could potentially be an illuminating first step for medical research.